Identifying Trilobites

By Cindy Smith

The Pioche Formation of eastern Nevada is world famous for its amazing preservation of trilobites. Very old trilobites, from the Lower Cambrian (542 – 521 million years old), almost the oldest on record.

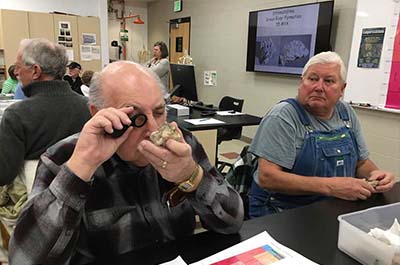

Stones ‘n Bones members got together to study and then identify seven species of Olenellus trilobites collected from the very boundary of their extinction event 521 million years ago. Due to a devastating change in the temperature and oxygenation of the ocean surface waters, the Olenellus sub-group died out, though other trilobites were able to adapt and survive.

Diana Biggs and Mary Chamberlain identifying Olenellus trilobites

Olenellids are considered a primitive trilobite with a thin exoskeleton, crescent-shaped eye ridges, and a variety of other anatomical features that provide diagnostic information, allowing us to identify them down to the species level. But it’s not easy because the preservation varies, as these features have been distorted by millions of years of pressure and movement. And because we don’t (yet) possess the uncanny ability that experienced paleontologists have developed to detect the nuanced details contained in the trilobite cephalon.

Harold and Christina Taylor, Matt Eaton, Andrew Smith, and Steve Wolfe

Matching diagnostic structures of various Olenellid trilobites

Working through the anatomical features to get to the genus/species.

Though some of our trilobite specimens were complete, most were fragments, and we focused only on the cephalon (the head). To determine the species, we noted the shape and length of the glabella (the raised lobe on the cephalon), the length and robustness of the eye ridge, the length and location of the genal spine, and the distance from the anterior tip of the glabella to the anterior margin of the trilobite. This is the simplified version of identification. There are many more structures and measurements that go into the scientific distinction that leads to species identification.

An excellent website with good charts on trilobite anatomy is: https://amazingzoology.com/anatomy-of-trilobites/

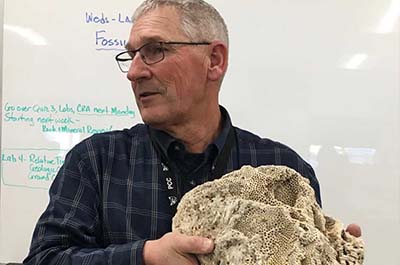

We also studied hypostomes, the hard mouth part found on the underside of the trilobite. These diagnostic structures vary enormously in shape due, apparently, to the type of feeding behavior and prey devoured by the trilobite. Like our patella (kneecap), which is attached to our limb bones by tendons and ligaments, the hypostome is also unattached to the trilobite itself and can sometimes be found separately on pieces of slate.

Some of our trilobites were collected from Ruin Wash, a lagerstätte (area of extremely good preservation and extraordinary fossils). These fossils were collected on a 2018 WIPS (Western Interior Paleontological Society) field trip led by Joe Dabelko and John Foster (author of “Cambrian Ocean World”). Other sites included Oak Springs, Klondike Pass, and Comet Shale Mine, all in either the Lower or Middle Cambrian Period.

As I watched our group tackle the identification process, I was again struck by the joy of learning. In such busy lives that we all lead, we make the time to come together to share not only an appreciation for the intricacy of trilobite anatomy, but even more so to marvel at the meticulous research done by many before us who share our passion for an understanding of once-living creatures.

Olenellus chiefensis cephalon. Note the pointed glabella tip, a wide space between the glabella and the anterior margin, and a parabolic shape (laterally compressed sides) to the cephalon. The long robust eye ridges on either side of the glabella are also diagnostic features.

Olenellus gilberti. This trilobite has a rounded glabella tip, a narrow space between the glabella and the anterior margin, and a more semi-circular cephalon.

More Articles from “Stones ‘n’ Bones Activities”

Fossil Boot Camp – Covid Style

Stones ‘n Bones of Fremont County traditionally presents two or three Fossil Boot Camp classes each year for school age students and adults. With COVID, that has proven a little difficult

Fossil Boot Camp for PCC Historical Geology Students

Fremont Stones ‘n Bones introduced 16 Pueblo Community College students to fossils in Steve Wolfe’s Historical Geology class.

Stones ‘n’ Bones With Villa Bella School’s 2nd Graders

“What do paleontologists do?” is the question we were asked to help answer for 50 second graders at Pueblo, Colorado’s newest elementary school on January 16, 2020.

The Close Relationship Between Man & Dog

Dr. Sue Ware returned to the Royal Gorge Dinosaur Experience for the second time, to the delight of 27 community members. She presented a program entitled “From your Campfire to your Bed: The Evolution, Importance & Relationship between Dogs and Humans”.

Fossil Boot Camp at PCC Mini-College

For the 5th straight year, Stones ‘n Bones presented Fossil Boot Camp to 31 senior citizens in the Fremont County community.

Stones ‘n’ Bones & the Enormous Egg

What happens when an entire elementary school reads the same book, The Enormous Egg, and asks Fremont County Stones and Bones to come in to help with the family night to celebrate the reading? A two-hour evening full of paleontology learning!

Introducing Geology Students to Fossils

How does Steve Wolfe, Historical Geology instructor at PCC-Fremont Campus, prepare his students for field season observations? One way is by introducing them to fossils

Identifying Trilobites

The Pioche Formation of eastern Nevada is world famous for its amazing preservation of trilobites. Very old trilobites, from the Lower Cambrian (542 – 521 million years old), almost the oldest on record.

Everything Begins With Mining

There are many ways to appreciate rocks. Many of us notice them simply for their color, texture and shape, irresistible and raw in nature.

Insects Trapped in Amber

Many of us are familiar with the high preservation of insects and leaves in the Green River Formation, a Colorado lagerstätte well known for field trips yielding magnificent fossils.